Author Bio

D. E. McElroy is an ordained Christian minister and spiritual researcher with decades of experience exploring the history of faith, mysticism, and the hidden stories behind religious movements. His works focus on uncovering truths often buried or distorted by political and institutional power, offering readers a clear, compassionate perspective on humanity’s spiritual journey.

Copyright

© 2025 D. E. McElroy-World Christianship Ministries All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means — electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise — without prior written permission of the author, except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews.

Index / Table of Contents

- Prologue – The Last Perfect

- Chapter 1 – The World Before the Cathars

- Chapter 2 – The Birth of the Cathar Movement

- Chapter 3 – Dualism and the Two Gods

- Chapter 4 – Jesus the Liberator

- Chapter 5 – The Way of the Perfecti

- Chapter 6 – The Growing Threat

- Chapter 7 – The Albigensian Crusade

- Chapter 8 – Montségur and the Last Stand

- Chapter 9 – The Inquisition’s Long Reach

- Chapter 10 – Legacy and Meaning

- Chapter 11 – Other Movements Rome Targeted

- Appendix A – Timeline of the Cathar Story

- Appendix B – Glossary of Cathar Terms

- Appendix C – Map of Cathar Strongholds

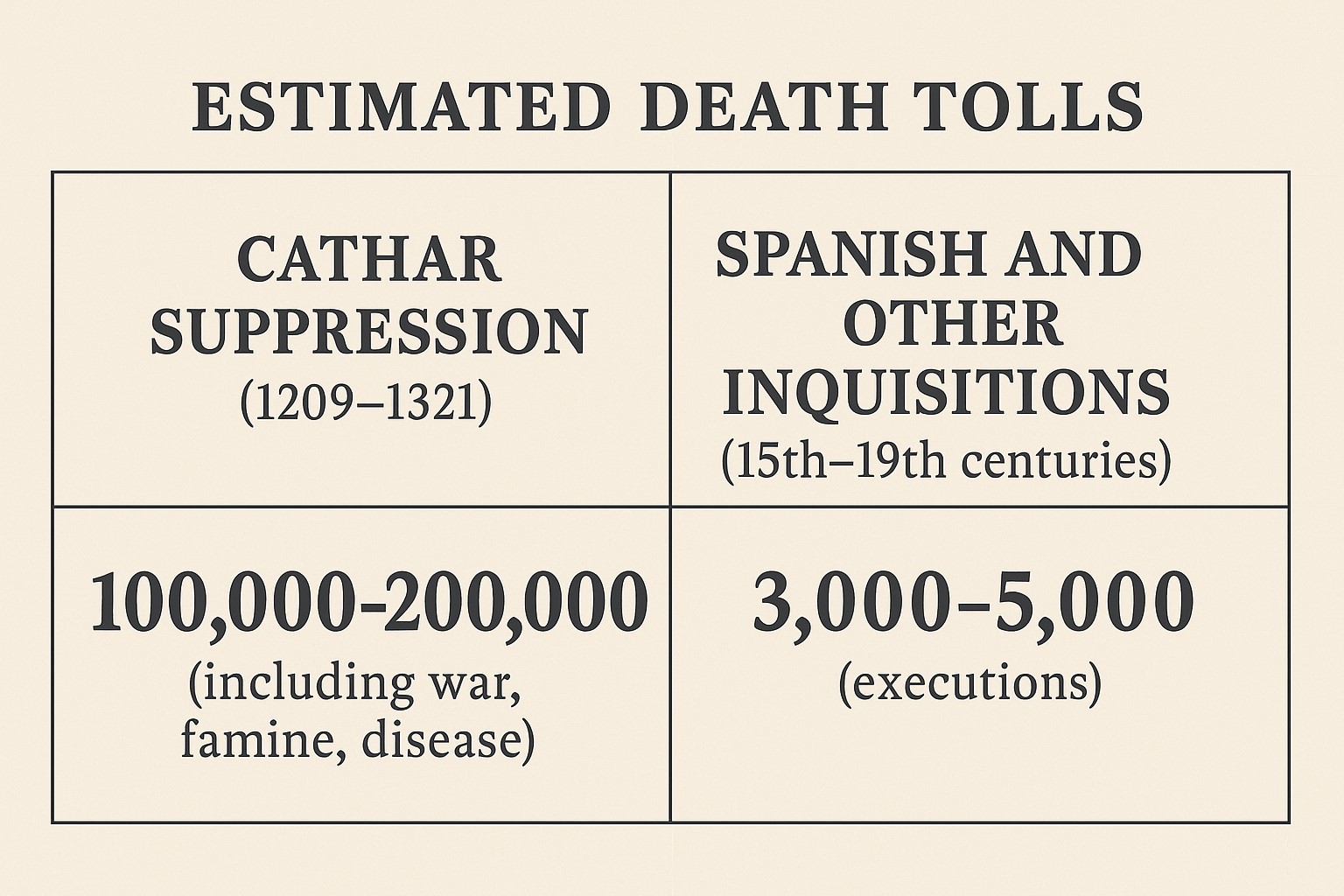

- Appendix D – Death Toll Comparison Chart

Prologue – The Last Perfect

The air over Villerouge-Termenès was heavy with woodsmoke and silence. It was autumn, the year of our Lord 1321, and the narrow streets of the village were lined with faces — some grim, some curious, some quietly weeping. In the center, bound between two soldiers, walked Guillaume Bélibaste, the last known Perfect of the Cathar faith.

He was gaunt from the long months of captivity, but his dark eyes burned with a strange, serene defiance. Bélibaste knew his sentence well: to be burned alive for the crime of heresy. The Inquisitors would not have called it a murder; to them, it was an act of purification. Yet Bélibaste had no illusions — this was not purification, but the final silencing of a way of life that had defied Rome for over a century.

They led him to the stake, where bundles of dry kindling waited. The executioner, a man who had likely lit such fires before, avoided Bélibaste’s gaze. Above them, the banners of the French crown and the Papal Inquisition flapped together in the wind — the twin forces that had crushed the Cathars, stone by stone, soul by soul.

As the priest read the formal sentence, Bélibaste lifted his head toward the watching crowd. His voice, surprisingly steady, carried across the square:

“This is not the end. The truth is not ashes. What burns here is flesh only — the spirit returns to God.”

They tied him fast to the stake, and the torch was set to the wood. The first smoke curled upward, mingling with the autumn wind. Somewhere beyond the hills stood the ruins of Montségur, the last great Cathar fortress, where in 1244 over two hundred Perfects had chosen fire rather than recant their faith. Now, with Bélibaste’s death, the Church could finally claim that the heresy of the Languedoc was finished.

But the embers would smolder in secret memory — in whispered stories told at night, in hidden symbols carved into stones, and in the stubborn longing for a Christianity unbound by Rome’s chains. The last Perfect was gone. The spirit of the Cathars was not.

Chapter 1 – The World Before the Cathars

In the early decades of the 12th century, Europe was a land of contrasts. The Catholic Church claimed to speak for God on earth, yet its cathedrals were gilded with wealth collected from the faithful. Kings and popes alike saw themselves as rulers by divine mandate, while the majority of their subjects worked the land in poverty, their lives ruled by feudal obligation and the cycle of planting and harvest.

It was an age when religious authority was rarely questioned openly. The Bible was locked away in Latin, a language the common people could not read. Faith was mediated through priests, and salvation was said to come only through the sacraments administered by the Church. To defy Rome was to defy God Himself — or so the priests declared from the pulpits.

The Catholic Church in the 12th Century

By this time, the Church had become the largest landowner in Europe, richer than many kings. Its hierarchy was vast and disciplined: bishops in stone palaces, abbots ruling over monasteries like feudal lords, and the Pope in Rome acting as the supreme authority over all Christendom.

Corruption was an open secret. Bishoprics were bought and sold. Many priests kept mistresses and lived far from the poverty they preached. The sale of indulgences — promises of reduced time in purgatory — had become a lucrative trade. To many devout Christians, it seemed the Church had strayed far from the humility of Jesus and His apostles.

Languedoc: A Different World

Far to the south, in the region known as Languedoc (stretching from the Pyrenees to the Rhône), life was different. Here, the towns were prosperous trading centers connected to the Mediterranean world. Culture flourished: troubadours composed love poetry, courts discussed philosophy, and tolerance for different beliefs was not unusual. In many towns, Catholics, Jews, and even Muslims conducted business side by side.

The nobility of Languedoc, such as the Counts of Toulouse, valued independence. They often resisted the control of northern France and the dictates of Rome. This independence extended to matters of faith — itinerant preachers were allowed to speak openly, and the people were more willing to listen to alternative interpretations of Christianity.

Seeds of a Spiritual Rebellion

It was in this fertile soil that whispers of a different gospel began to spread. From the Balkans and Italy came traveling teachers carrying a message both simple and radical: the world of flesh and matter was the creation of a false god, and the true God was pure spirit. Jesus had come, not to build a church of stone, but to free the soul from the prison of the material world.

This was a faith stripped of Rome’s pomp and ritual. There was no need for tithes, no veneration of relics, no priestly absolution. The true baptism was not in water but in spirit — a single rite called the Consolamentum, a passing of divine truth from one soul to another.

By the mid-12th century, this movement had a name in the tongues of its enemies: Cathars — “the pure ones.” And though the Church in Rome would call them heretics, in the hills and towns of Languedoc they were welcomed as men and women of integrity, living the gospel they preached.

Chapter 2 – The Birth of the Cathar Movement

The exact origins of the Cathars are shrouded in mystery, a blend of history and rumor that stretches across continents. Some medieval chroniclers claimed they were heirs to an ancient heresy, a reincarnation of the early Gnostics who had been driven underground after the Church consolidated power in the 4th century. Others linked them to the Bogomils of the Balkans — a Christian dualist sect that arose in 10th-century Bulgaria, preaching that the world was a battleground between the God of Light and the Lord of Darkness.

Whether through trade, migration, or missionary work, Bogomil ideas traveled westward along the old Roman roads and Mediterranean trade routes. By the 11th century, they had reached northern Italy and southern France, carried by wandering preachers who rejected both papal authority and the elaborate rituals of the Catholic Church.

From the Balkans to Languedoc

Languedoc’s openness to new ideas made it a natural home for these teachings. Here, the Perfecti — the fully initiated Cathar spiritual leaders — found safe haven among sympathetic lords and townsfolk. Dressed simply, traveling in pairs, they preached in the language of the people, not in the inaccessible Latin of the clergy.

They carried no swords, demanded no tithes, and lived according to the words they spoke. For many who had grown weary of the hypocrisy they saw in the Catholic clergy, these humble men and women seemed closer to the example of Christ than the robed bishops in their palaces.

A Radical Gospel

The Cathar message was simple but revolutionary:

- The material world was the creation of a false god — the Demiurge — and was a place of suffering and corruption.

- The true God was entirely spirit, and the human soul was a fragment of that divine essence, trapped in flesh.

- Jesus was a purely spiritual being, who had come not to redeem the flesh but to show souls the path back to God.

- There was no Hell in the Catholic sense; punishment was to be reborn into the suffering of the material world again and again until freed.

The sole Cathar sacrament, the Consolamentum, could be given at any time — often near death — as a final liberation from the cycle of reincarnation. This rejection of Catholic sacraments cut to the heart of Rome’s authority, for it undermined the Church’s claim to be the sole mediator between God and humanity.

Why the Church Took Notice

At first, Rome underestimated the Cathars. Local bishops attempted debates and sermons to refute them, but the Cathar preachers were eloquent, steeped in scripture, and unshakable in their faith. By the 1170s, whole towns in Languedoc had more Cathar believers than Catholics, and noble families openly sheltered the Perfecti.

What made the movement truly dangerous to Rome was not simply its theology, but its moral credibility. Where many Catholic priests were known for corruption and indulgence, Cathar Perfecti lived in poverty and chastity, cared for the sick, and traveled tirelessly to minister to the poor. They embodied the very virtues the Church claimed to uphold but so often betrayed.

By the late 12th century, the Vatican’s patience was wearing thin. What began as an attempt at persuasion would soon turn into a war without mercy.

Chapter 3 – Dualism and the Two Gods

To understand the Cathars, one must first understand the dualism that defined their faith — a vision of reality split between two irreconcilable forces.

The Good God and the Evil God

In the Cathar view, there were two eternal principles:

- The Good God – Pure, infinite Spirit, the creator of the invisible realm of light, truth, and peace. This was the God Jesus revealed — a God of compassion and liberation.

- The Evil God – Also called Rex Mundi (“King of the World”) or the Demiurge, this being created the material universe, including the earth and all fleshly life. He was the author of suffering, corruption, and death.

This was no symbolic contrast for the Cathars — it was literal. The Good God had nothing to do with the creation of the physical world. The heavens of spirit and the prison of matter were at war.

The Fall of the Soul

According to Cathar teaching, the human soul was a fragment of divine light, pure in its origin, but trapped in the material realm through the schemes of the Evil God. Birth into a human body was not a blessing, but a captivity — and death, if unredeemed, meant returning again in another body to suffer anew.

This was why they rejected the Catholic doctrine of bodily resurrection. To them, salvation was not the restoration of flesh, but the escape from it.

Jesus the Liberator

In the Catholic Church’s teaching, Jesus was both fully divine and fully human, born into the world to die for the sins of humanity. For the Cathars, this was unthinkable. They believed Jesus never took on corrupt flesh at all — He appeared in a purely spiritual form, visible to human eyes but not subject to physical needs or death in the ordinary sense. His mission was not to pay for sins through sacrifice, but to reveal the truth: that the soul’s home was in the realm of the Good God, and that the Church’s claim to control salvation through its sacraments was false.

Why This Threatened Rome

If the Cathars were right, then:

- The Creator of the material world — the God invoked in much of the Old Testament — was not the true God of love and spirit.

- The crucifixion was not a divine transaction for sin, but a spiritual drama with no need for the Church’s mediation.

- Salvation was available through spiritual awakening (gnosis), not through baptism, confession, or Mass.

In short, the entire foundation of Catholic authority crumbled under Cathar theology.

The Battle for Allegiance

The Church responded with predictable fury. To Rome, Cathar dualism was blasphemy, a direct assault on the unity and omnipotence of God as taught in Catholic creed. The refusal to venerate the cross, to take oaths, or to honor the sacraments was painted as proof that the Cathars were not simply mistaken Christians, but dangerous enemies of Christendom.

The people of Languedoc, however, saw things differently. Many found in Cathar teaching a freedom from fear — no eternal hellfire, no compulsory tithes, no corrupt priest deciding their fate. Only a personal, spiritual journey toward the God of light.

That freedom would soon come under fire, quite literally.

Chapter 4 – Jesus the Liberator

For the Cathars, Jesus was not a king enthroned in splendor or a sacrifice to appease an angry God. He was a liberator of souls, the living voice of the Good God, sent into the shadowed prison of the material world to awaken humanity to its true origin.

A Spiritual Messiah

The Catholic Church taught that Jesus was born in Bethlehem as the Son of God made flesh, both fully divine and fully human. The Cathars rejected this outright. They saw Jesus as entirely spiritual — a being of light who only appeared to have a body so that He could walk among people and teach them directly. This belief, known to theologians as docetism, meant that:

- He did not experience hunger, fatigue, or physical pain in the way humans did.

- The crucifixion, though witnessed by many, was not the end of His existence — for He was never truly bound by flesh to begin with.

The Message, Not the Sacrifice

To the Cathars, the central truth of Jesus’ mission was not that He died for humanity’s sins, but that He taught humanity how to escape the cycle of rebirth and return to the realm of the Good God. This shift from atonement through blood to liberation through knowledge was a direct challenge to Catholic theology, which centered its entire system of salvation on the cross.

In Cathar sermons, the emphasis fell on:

- The Sermon on the Mount — love enemies, reject violence, live in purity of heart.

- The rejection of worldly power — “My kingdom is not of this world” was taken literally.

- The refusal to swear oaths or take up arms — an uncompromising stance used against them as “disloyalty.”

Jesus and the Consolamentum

The Consolamentum — a laying-on of hands with the Lord’s Prayer — was the single Cathar sacrament. Cathars believed Jesus Himself had given this rite to His apostles, not as a formal ritual for a church to control, but as a direct spiritual empowerment. To receive it was to step into Jesus’ path — to renounce the world of the Evil God and live as a citizen of the Kingdom of Spirit.

Why This View Was Dangerous

In Rome’s eyes, such teachings were heresy and rebellion: they stripped the crucifixion of unique salvific power, bypassed the priesthood, and taught that knowledge and purity of life could achieve what the Church claimed only the sacraments could provide.

To the Cathars, Jesus’ example was simple: live without violence, without greed, without lust — and remember that the soul’s home is not the corrupt realm of matter but the light of the Good God.

Chapter 5 – The Way of the Perfecti

Among the Cathars, there were two groups:

- The Believers (credentes) – the majority, who accepted Cathar teachings but lived ordinary lives.

- The Perfect (perfecti) – the spiritual elite, fully initiated through the Consolamentum and bound to a life of strict discipline.

The perfecti were not priests in the Catholic sense. They were living examples of the life Jesus had called His followers to lead — as the Cathars understood it — and they were expected to embody purity in every word and deed.

The Vows

Receiving the Consolamentum meant a complete renunciation of the material world and its corruptions. The perfecti pledged:

- Poverty – owning nothing beyond simple clothing and a few necessities.

- Chastity – abstaining from sexual relations entirely.

- Non-violence – refusing to kill, even in self-defense; they would not swear oaths or serve in war.

- Vegetarianism – avoiding meat, since it was part of the cycle of death that bound the soul to matter.

Breaking these vows was unthinkable — it was believed to imperil the soul’s chance of escaping rebirth.

Ministry Without a Church

The perfecti had no grand cathedrals. Their ministry was done in homes, workshops, or under open skies. They traveled in pairs, preached in the local language, offered the Consolamentum after long instruction or at the deathbed, and cared for the sick and poor.

The Believers and the Deathbed Consolamentum

Most believers aimed to receive the Consolamentum near death, ensuring liberation before another rebirth. This made the perfecti indispensable; without them, the sacrament could not be given.

Why They Were Feared

Their integrity — no fees, no oaths, no violence — exposed the Church’s corruption and undermined both ecclesial and royal power. To the people, they were saints. To Rome, they were the core to be destroyed.

Chapter 6 – The Growing Threat

By the final decades of the 12th century, the Cathar movement was a social and spiritual force in Languedoc. From peasant farmers to powerful nobles, thousands embraced its teachings; many more sympathized.

Catharism in City and Country

In Toulouse, Albi, and Carcassonne, Cathar preachers addressed crowds in marketplaces. In the countryside, gatherings met in barns or under the open sky. In some areas, Catholics were outnumbered; nobles gave escort and shelter to the perfecti.

The Church’s Early Response

Rome sent preachers, but their finery contrasted with Cathar simplicity. Debates often went poorly for the bishops. Attempts to mimic austerity rang hollow beside the perfecti’s lived example.

Papal Alarm

Innocent III, elected in 1198, saw a political crisis: reject the sacraments and Rome’s authority collapses; shelter heretics and papal influence in the south dissolves. By 1204 legates tried negotiation and debate — with little effect.

The Murder That Changed Everything

In 1208 the legate Pierre de Castelnau was assassinated on the Rhône. Suspicion fell on allies of Raymond VI of Toulouse. Innocent excommunicated Raymond and proclaimed a crusade against the heresy at home.

Chapter 7 – The Albigensian Crusade

When Innocent III proclaimed the crusade in 1209, nobles from the north assembled — some seeking faith’s reward, others lands and plunder. Their target: fellow Christians branded heretics.

Béziers – “Kill Them All”

In July 1209, Béziers refused to betray its Cathars. The army stormed the town. Catholics and Cathars alike were butchered; homes and the cathedral burned with refugees inside. The legate Arnaud Amalric is recorded as saying, “Kill them all; God will know His own.” Chroniclers claimed 20,000 dead; modern estimates are 7,000–10,000.

Carcassonne – Stripped and Banished

Weeks later, Carcassonne fell after siege. Inhabitants were expelled nearly naked in the summer heat. Simon de Montfort received the city and its lands.

Minerve – Fire and Refusal (1210)

Over 140 perfecti refused to recant and were burned alive, singing as flames rose.

Lavaur – The Pit

At Lavaur, over 400 were executed in a single day; Lady Guerin de Lavaur, who sheltered perfecti, was thrown into a well and stoned.

Simon de Montfort’s Campaign

For a decade de Montfort razed villages, burned crops, poisoned wells, mutilated prisoners, and starved towns. Terror was policy; resistance was to be unthinkable.

The First Phase Ends

By 1215 most strongholds had fallen. The Lateran Council confirmed conquests; northern lords kept Cathar lands. The faith retreated to hills and redoubts — foremost Montségur.

Chapter 8 – Montségur and the Last Stand

By the early 1240s, open Cathar life had vanished, replaced by secrecy. One bastion remained in plain sight: the eagle’s nest of Montségur.

A Fortress in the Sky

Its walls perched on a sheer rock in the Pyrenees foothills, reached only by a narrow path. Within gathered around 200 perfecti, supporters, and resisting nobles.

The Siege of 1243–1244

Royal and Church forces encamped below, cutting supply lines. Winter hunger tightened belts around empty stomachs. The perfecti prayed and prepared for martyrdom.

Betrayal and Surrender

Terms spared soldiers and non-Cathars; those who refused to renounce were given time. Many believers sought the Consolamentum, choosing the path of fire.

The Field of the Burned

On March 16, 1244, more than 200 men and women entered a fenced pyre at the mountain’s foot. They refused to recant. Torches were set; hymns rose over the flames. The place is still called Prat dels Cremats — the Field of the Burned.

Montségur’s fall ended organized resistance; its meaning outlived the ashes.

Chapter 9 – The Inquisition’s Long Reach

The flames did not end the faith. Survivors fled to forests and foreign valleys; others stayed, risking everything. The Church turned to systematic eradication through the Papal Inquisition, formalized by Gregory IX in 1231.

Machinery of Fear

- Compulsory summons (non-appearance meant guilt).

- Public interrogations to extract names.

- Prison in dark, airless cells.

- Torture to force confessions.

- Confiscation of property, ruining families.

Cutting the Spine

The perfecti were hunted. Some were betrayed for coin; others captured after mountain chases. Many burned. In 1321 Guillaume Bélibaste was executed at Villerouge-Termenès — remembered as the last known perfectus.

Believers’ Lot

Recant publicly and wear the yellow cross, or face prison and the stake. Some complied outwardly and kept fragments in secret. By the late 14th century, open Catharism was gone — but memory persisted.

Chapter 10 – Legacy and Meaning

When the last perfectus died in flames, Rome declared victory; the French crown absorbed the south. Official chronicles called the Cathars a solved problem. But victor’s history is never whole.

A Faith Remembered

- Villagers spoke of Bons Hommes and Bonnes Femmes — healers and humble wanderers who lived as Christ lived.

- Ruins on ridges were pointed out as shelters of a pure and gentle faith.

- Folk songs recalled people who refused to betray conscience even at the cost of life.

Influence on Modern Spirituality

- Rejection of materialism as a spiritual path.

- Direct access to divine truth without institutional mediation.

- Non-violence, compassion, and shared spiritual leadership by women and men.

Myths and Mysteries

Stories lingered of a treasure smuggled from Montségur — not gold but teaching or relic, a symbol that light survives power’s darkness.

Lessons for Our Time

- When faith arms politics, cruelty is excused.

- When dissent is silenced, truth hides and waits.

- When conscience faces corruption, even defeat sows seeds.

Chapter 11 – Other Movements Rome Targeted

This chapter places the Cathars within a wider pattern: whenever groups claimed direct access to God, challenged church wealth, or lived outside tight control, coercion followed — from book burnings and confiscations to torture, exile, and mass killing.

1) Pagan Cults in Late Antiquity (4th–5th c.)

What they were: Traditional Roman, Greek,

and Egyptian religions.

Why targeted: After Christianity became the

Empire’s official faith, bishops and emperors saw old cults as

rivals.

What happened: Anti‑pagan laws; temples

closed or destroyed (e.g., the Serapeum in Alexandria,

391–392); priests dispersed; altars smashed; some killings

during riots.

2) Manichaeans (3rd–6th c., later echoes)

What they taught: Strict dualism of Light

vs. Darkness with ascetic ethics.

Why targeted: Branded dangerous heresy;

imperial laws singled them out.

What happened: Property seizures, banishment,

occasional death penalties; books burned; adherents hunted by

church and imperial officials.

3) Priscillianists (4th–6th c.)

What they taught: Reformist, austere

Christianity in Spain with ascetic ideals.

Why targeted: Accusations of magic and

heresy; pressure from bishops.

What happened: Priscillian of Ávila

and companions executed at Trier in 385—often

cited as the first executions for heresy tied to church

politics.

4) Waldensians (12th–17th c.)

What they taught: Apostolic poverty, lay

preaching in the vernacular, Scripture above church wealth.

Why targeted: Preaching without permission

and public criticism of clergy.

What happened: Condemnations by councils;

periodic crusades and massacres; villages burned; the Piedmont

Easter massacre (1655) saw brutal killings and

expulsions.

5) Beguines & Beghards / “Free Spirit” cases (13th–14th c.)

What they were: Lay women (Beguines) and men

(Beghards) living simply in prayer and service, outside

regular orders.

Why targeted: Independence worried

authorities; some mystical writings were condemned.

What happened: Marguerite Porete

burned in 1310 for The Mirror of Simple

Souls; the Council of Vienne

(1311–12) condemned certain teachings; houses closed; members

jailed or expelled.

6) Spiritual Franciscans / Fraticelli (14th c.)

What they taught: Radical poverty; Christ

and the Apostles owned nothing.

Why targeted: Defied papal rulings on

property and obedience.

What happened: Trials, imprisonments, and

burnings (notably 1318); communities

dismantled.

7) Knights Templar (1307–1314/1312)

What they were: A military religious order

from the Crusades.

Why targeted: The French crown coveted their

wealth and feared their power; heresy charges used as a

political weapon.

What happened: Mass arrests; torture‑based

confessions; papal dissolution of the order; Grand

Master Jacques de Molay burned in 1314.

8) Hussites (early 15th c.)

What they taught: Reform inspired by Jan

Hus—vernacular preaching, moral renewal, communion

in both kinds.

Why targeted: Challenged clerical power and

corruption.

What happened: Hus burned in 1415;

a series of papal crusades (1419–1434) devastated Bohemia with

sieges and massacres.

9) Bogomils & “Bosnian Heresy” (10th–15th c.)

What they taught: Balkan dualist currents

akin to Cathar critiques of the material world and church

wealth.

Why targeted: Threat to Byzantine and Latin

churches and to royal control.

What happened: Pressures, forced conversions,

and crusading expeditions into Bosnia in the 13th century;

communities dispersed or absorbed.

Why it matters: The Cathars were not an isolated case; they fit a broader pattern where spiritual renewal outside institutional control met repression—sometimes by sermon and edict, often by sword and fire.

Appendix A – Timeline of the Cathar Story

- c. 950–1050 – Rise of the Bogomils in Bulgaria, preaching dualism and rejecting Catholic and Orthodox authority.

- 11th Century – Dualist ideas spread into northern Italy and southern France via trade and itinerant preachers.

- 1140s–1160s – Cathar communities established openly in Languedoc; perfecti minister to growing congregations.

- 1170s–1190s – Cathar numbers swell; in some towns, they outnumber Catholics. Noble families offer protection.

- 1198 – Pope Innocent III begins efforts to suppress Catharism through debate and persuasion.

- 1208 – Papal legate Pierre de Castelnau assassinated; Innocent III calls for a crusade against the Cathars.

- 1209 – Béziers massacre (“Kill them all”) and the fall of Carcassonne mark the brutal start of the Albigensian Crusade.

- 1210 – Mass burnings at Minerve and Lavaur; Simon de Montfort emerges as crusade leader.

- 1215 – Fourth Lateran Council confirms crusader gains; northern French lords take Cathar lands.

- 1229 – Treaty of Paris ends main phase of war; Languedoc brought under French crown. Inquisition begins systematic hunt for heretics.

- 1243–1244 – Siege and fall of Montségur; over 200 Cathar perfecti burned.

- 1321 – Execution of Guillaume Bélibaste, last known perfectus, at Villerouge-Termenès.

- 14th Century onward – Catharism survives only in secret memory and folklore.

Appendix B – Glossary of Cathar Terms

- Cathar

- From Greek katharoi, “the pure ones”; name given by outsiders.

- Perfecti (Perfects)

- Fully initiated Cathar leaders living under vows of poverty, chastity, and non-violence.

- Credentes (Believers)

- Lay followers who often sought the Consolamentum on the deathbed.

- Consolamentum

- Sole Cathar sacrament, conferring spiritual baptism by laying on of hands.

- Dualism

- Two eternal principles: Good God (Spirit) vs. Evil God/Demiurge (creator of matter).

- Demiurge / Rex Mundi

- The false creator who traps souls in flesh.

- Albigensian Crusade

- Papal-sanctioned campaign (1209–1229) to eradicate Catharism.

- Inquisition

- Papal judicial system for identifying, interrogating, and punishing heresy.

Appendix C – Map of Cathar Strongholds

Appendix D – Death Toll Comparison Chart